Mandarin jackets are trending

Appropriation v appreciation

The first time I was clued in to the “mandarin” jacket trend was at a very (very) nice store in Amsterdam’s 9 Streets whilst shopping last fall. In sifting through their collection of items I wish I could afford, one of the jackets I was dying to try on was a cropped wool jacket with a standing collar and embroidered cord buttons — and upon checking the tag I was equally confused by the price (€725) and the name.

Listen: I don’t mean to sound condescending here but I feel like a general rule of thumb should be that if you find something in an uber white western context with a vague name from another country or culture — the very least we can do is a quick Google search.

And “Mandarin Jacket” was definitely raising some red flags.

And yes: after a quick google search and a scroll past the luxury/designer ‘mandarin’ jackets available for purchase, you would find a wikipedia article on the tang (not mandarin) jacket — a jacket that features a mandarin collar and frog (or pankou) closures.

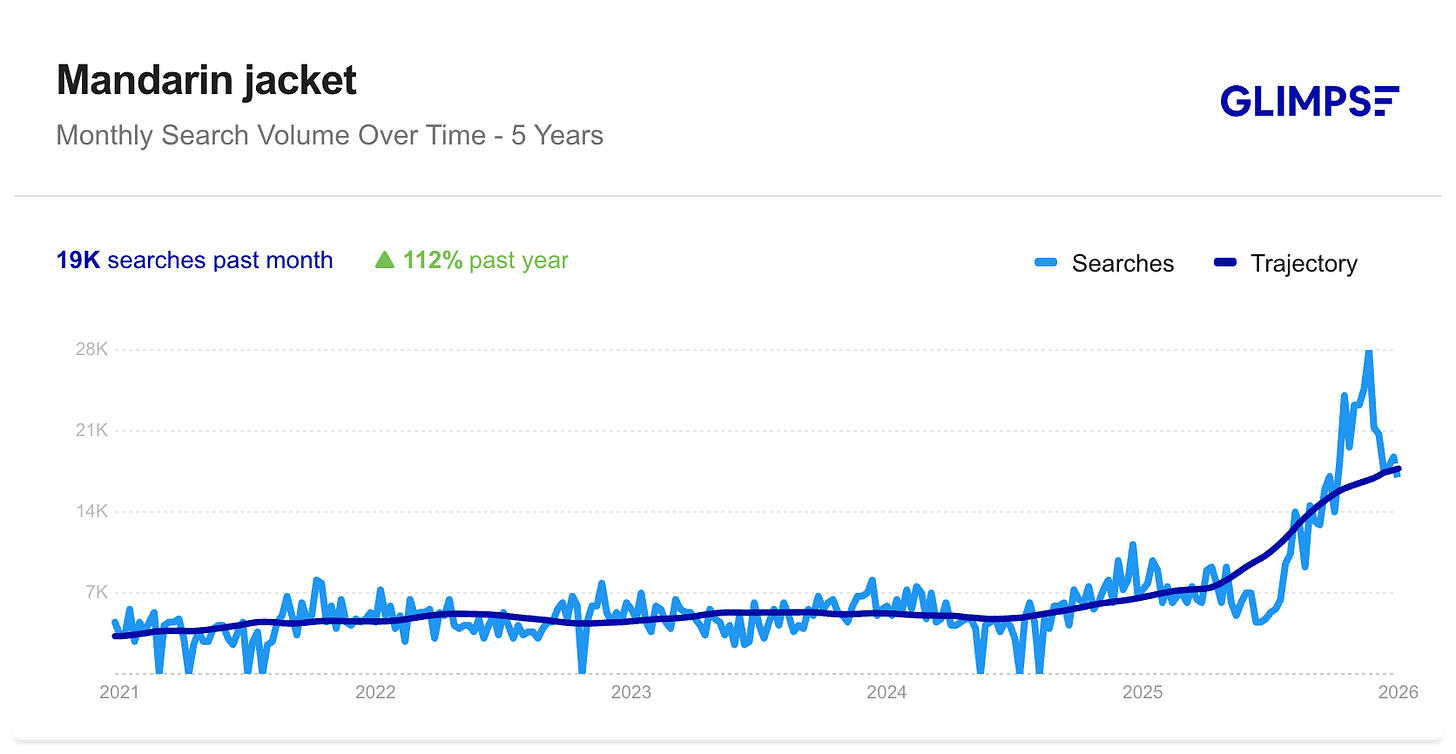

So — while Mandarin jackets don’t technically exist, they have continued to be an ‘2026 it-girl staple’ as some publications have put it — garnering 19k searches in the past month, up 112% in the past year.

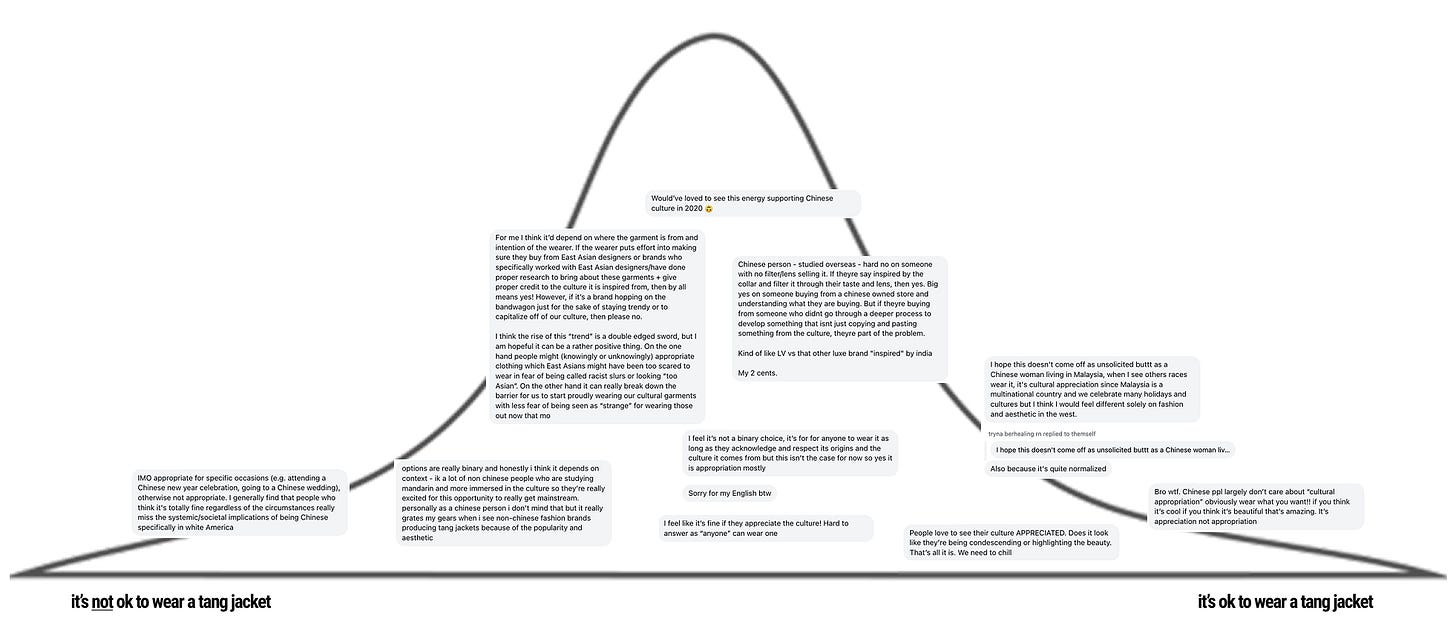

After putting out a video showing the contrast (tldr: look this thing is trending, but trending under the wrong name) I got a ton of feedback from Chinese viewers on the topic.

So! Instead of sheepishly asking your Chinese friends if it’s ok to wear a tang jacket — I have collected the full spectrum of opinions from my DMs (with permission of course to include them here).

I also spoke with Michelle She for her perspective on the conversation. Michelle is the founder of Cult of 9, a brand that explores Chinese design language through a contemporary lens while actively reframing what “Made in China” means in a Western context. By centering craftsmanship, material integrity, and the people behind the process, her work challenges the assumptions often attached to Chinese-made pieces and highlights the depth and value behind it.

The majority of the opinions sat somewhere in the middle of ‘you shouldn’t wear a tang jacket’ and ‘anyone can wear a tang jacket’ — highlighting the importance of understanding what you are wearing and where it comes from before putting it on your body.

As Michelle puts it:

I think the conversation around cultural appropriation often misses an important distinction between aesthetic extraction and cultural participation. The issue isn’t who is wearing something but it’s whether the craft, context, and people behind it are respected and supported by the wearer.

To me, cultural appreciation looks like shopping small, understanding where a garment comes from, producing in the place where the craft lives, and giving credit (economically and culturally) to the people behind it. Chinese culture isn’t something that needs to be hidden or protected through exclusion. It deserves to be appreciated globally, and that visibility is an important step toward soft power, respect, and ultimately reducing future racism against Chinese people.

The main problem is that western brands are lifting (and profiting) from Chinese culture without giving proper credit or context.

From @amysuuun: Personally as a Chinese person I don’t mind that but it really grates my gears when I see non-Chinese fashion brands producing tang jackets because of the popularity and aesthetic.

From AT: Hard no on someone with no filter/lens selling it. If they’re say inspired by the collar and filter it through their taste and lens, then yes. Big yes on someone buying from a chinese owned store and understanding what they are buying. But if they’re buying from someone who didn’t go through a deeper process to develop something that isnt just copying and pasting something from the culture, they’re part of the problem.

Perceptions of cultural appropriation are different for Chinese people living in China versus outside of China.

From Michelle: I’ve noticed a real divide between perspectives. Many Chinese people raised in the West feel protective of these symbols because of lived experiences with racism and stereotyping. Meanwhile, many artisans in China want their work to be seen, valued, and sustained — invisibility is often the greater fear. Sharing culture, when done properly, isn’t exploitation to them; it’s recognition.

There is the double edge sword of Chinese people not wanting to wear the garment in the west.

From IJ: I think the rise of this “trend” is a double-edged sword, but I’m hopeful it can lead to something positive. On one hand, people may, knowingly or not, appropriate clothing that East Asians might have felt too scared to wear before, out of fear of being called slurs or looking “too Asian.” On the other hand, it can also break down barriers and make it easier for us to proudly wear our cultural clothing, with less fear of being seen as “strange” for expressing who we are.

I had this (unknowingly) confirmed by a friend when we were thrifting in London. I pulled out a blue silk qipao and asked her if she thought it was weird when white girls wore them. She explained that it was kind of the opposite — that it seemed “fashionable” when white girls wore one but that she would be labelled as ‘too asian’ or not westernized enough if she wore one.

On the opposite side of the spectrum, some people say that it is never ok to wear traditional Chinese clothing for fashion purposes.

From GM: IMO appropriate for specific occasions (e.g. attending a Chinese new year celebration, going to a Chinese wedding), otherwise not appropriate. I generally find that people who think it’s totally fine regardless of the circumstances really miss the systemic/societal implications of being Chinese specifically in white America.

There is a need to recognize the craftsmanship coming out of the region.

From Michelle: From my experience, many craftspeople in China understand that there will always be some degree of cultural translation. Crafted clothing is a form of art, and art is inherently open to interpretation. What matters is that the story of the piece is not erased in that translation. When a garment is made with intention, fairly produced, and rooted in the traditions it draws from, that story carries through to how the wearer feels and how they present themselves to the world.

This also comes at an interesting time when Chinese culture and influence is increasing in the west (honestly the chinamaxxing memes are great) and I’ve pulled together my three favorite things I’ve read on the broader trend from people more qualified than I.

Final thing — why would I put this together? I am obviously not the expert here and have very little authority on when a fashion trend is appreciation versus appropriation.

Being very honest and candid here: I’ve been wanting to wear a qipao for years. The Chinese restaurant in the small Canadian town I grew up in used to have these embroidered brocade table cloths (with a glass top as to not ruin them) and I would bring printer paper from home and attempt to trace the embroidered flowers, animals, and characters while we waited for our food. I was around 10 and shopping secondhand (it was value village lol) when I came across a red and gold qipao (I didn’t know that that was what is was called at the time, but was nonetheless super excited to find a dress that had the same embroidery and patterns as the table cloths) and added it to our cart. My aunt who I was shopping with said that I would be ‘racist’ if I wore it — and put it back on the rack. ANYWAYS boohoo for me — been trying to decipher this ever since.

I really appreciate this conversation! Super interesting opinions. As a Latina woman I definitely want to share my culture but not when non Latin companies are profiting without doing their due diligence. Culture is meant to be shared and fashion is a great way to express that.

I was all prepared to do the whole "it's actually called..." but then I read this and was pleasantly surprised.